I'm Still Standing

Welcome to February, everyone’s favorite month because you get an issue of Crypto Curious every 14 days instead of every 15.25 days! I think we are finally over the FTX focus for a little bit. I did read in the Palo Alto Daily Post, however, that Sam Bankman-Fried now has a 75 pound German Shepard who is trained to attack with a special code word. This, of course, raises the question of what the code word is. I’m installing “Caroline” as the favorite at +275, “Bahama” at +500 and “Ponzi” at +600. What are your guesses?

🟢 Not Dead Yet

(Big Idea: Traction)

In March 2000, the Nasdaq Index peaked at 5,132. eBay sported a P/E of 1380, Amazon wasn’t profitable so it didn’t have a P/E and Lycos was valued at $10 billion. A little more than a year later, it bottomed at 1,423, down 72%. In 2001, I’m sure some people thought the Internet was dead, a fad that had run its course. I’m biased since I had already worked for three different Internet companies at that point, but I think most people could recognize the potential, even if Pets.com had definitely proven that shipping dog food was an idiotic idea and Kozmo.com showed that instant food delivery could never work.

Similarly, Ethereum peaked on November 10, 2021 and is currently down 67% from that high. And there seem to be plenty of people that are joyously convinced that NFTs are all dead and crypto is dying. Personally, I’m pretty convinced that we are in crypto’s 2001 moment. The bubble has burst and we may settle in for a less manic period of building, but this technology isn’t going to disappear. As a data point, a new report shows that the number of developers actively working on crypto grew 5% year over year, despite prices being way down.

We’ve talked about it before, but I believe that part of the reason that crypto is misunderstood is that, at least right now, it is a far better experience for developers than consumers. For developers, features like composability (I can easily build new things using pre-built code and protocols like Legos), permisionlessness (I can build and launch without asking permission) and trustlessness (I know that the underlying foundations will continue exist and be available) all make for an exciting environment.

Developer involvement then is a great measure of the health of the crypto ecosystem broadly as well as providing insights into which specific projects are doing especially well. And while any number can be gamed, because crypto is inherently open source, all crypto code bases live in repositories on GitHub that can be easily viewed and analyzed. Electric Capital, a crypto VC fund, has graciously (and brilliantly) aggregated this data into an annual report that just came out for 2022.

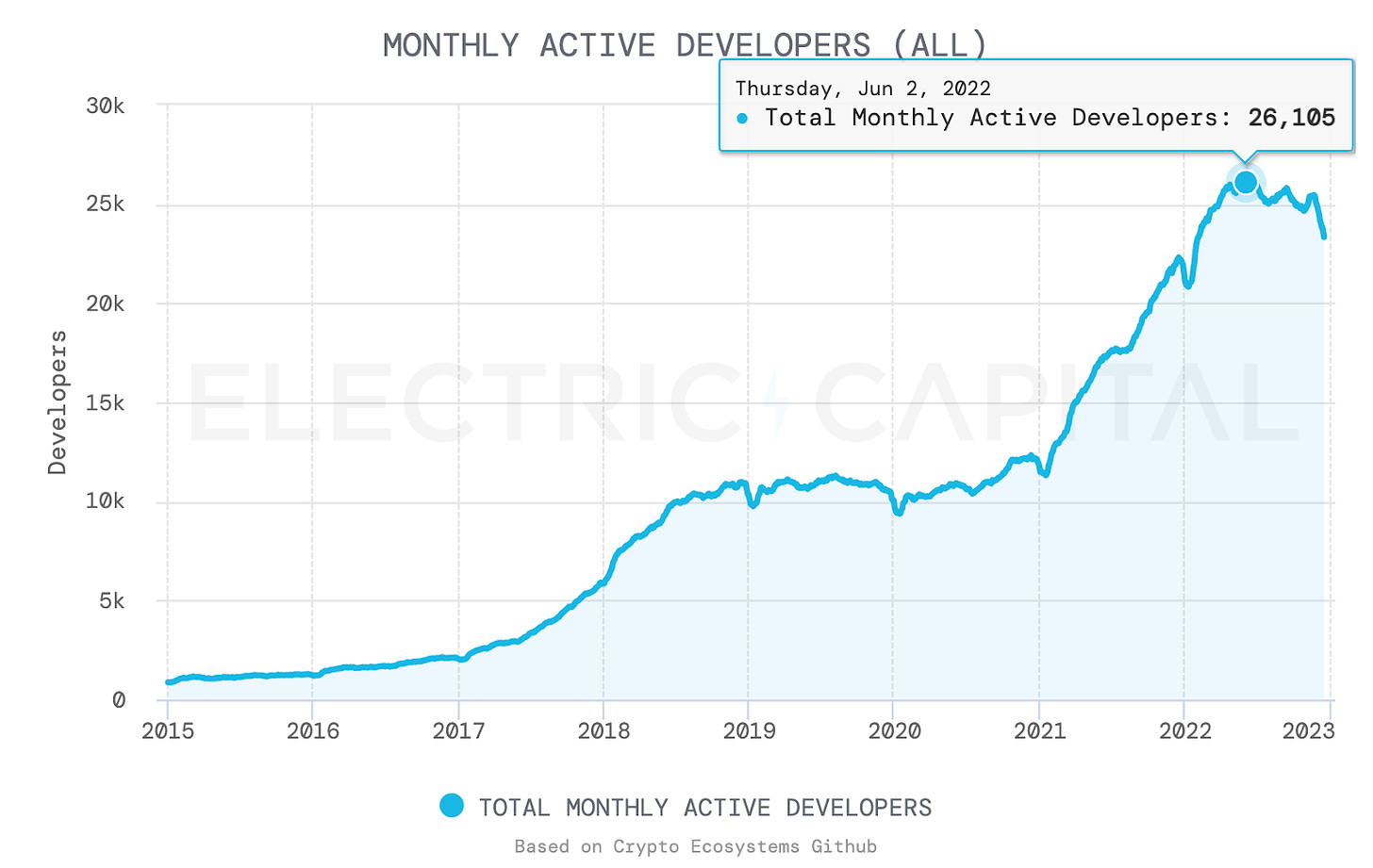

Not surprisingly, the total number of active developers peaked in June 2022, literally days before Etheruem hit its low price for this cycle:

But the overall trends are massively bullish. 2022 saw the largest influx of new crypto developers in history. Full time developers are the fastest growing segment, have been the most stable and contribute a larger percentage of code than ever before.

Growth slowed in 2022 compared to the previous two years, but has been similar to previous bear cycles. In 2018, only two ecosystems (Bitcoin and ETH) had over 100 developers. In 2022, we have dozens. Solana, Polkadot, Cosmos and Polygon all have over 1,000 monthly active developers.

Now, are some of these developers using their skills to bring a new dog coin to Solana? Sadly, yes. Apparently, if Bitcoin has Dogecoin and ETH has Shiba Inu, Solana needs its own crap coin. [Expert hint: You should hire some Bulgarian developers to build a dog-themed chain for Cosmos, that is clearly next.] But then again, the U.S. economy simultaneously brings us both the miracle of the mRNA vaccine as well as $1,000 Balenciaga Crocs so perhaps BONK coin is the price you pay for crypto innovation.

I have only a vague notion of what may get built in this crypto cycle, just as I failed to predict Grindr billboards on 101, but I have broad faith that more developers broadly equals more interesting innovation.

🟦 NFTs All Around Us

(Big Idea: NFT Innovation)

OK, quick quiz. Which of these NFTs do you like the most?

Option 1:

Option 2:

Option 3:

Please tell me you voted for #2! If so, HA!, we’ve actually switched your NFT for Folger’s crystals! Option #2 is actually the carpet from the Holiday Inn Express in Dubuque, Iowa. I know, I know, all of you probably thought Dubuque’s art scene ended with their downtown murals, but that’s what’s wrong with Coastal Elites.

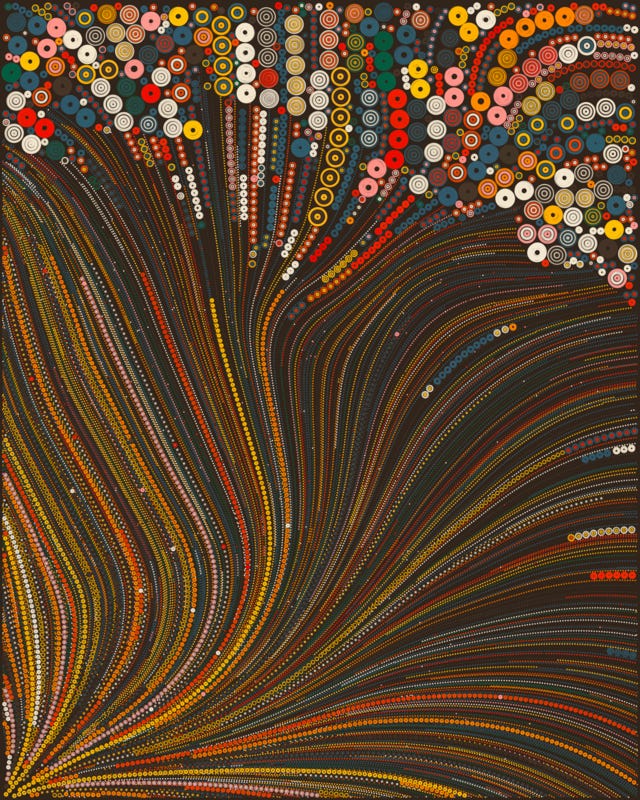

I was back in Dubuque last week for my uncle’s funeral (the world’s strongest man will be much missed). Google Maps calls the Holiday Inn “unassuming lodging,” but I couldn’t help notice the hallway carpet’s striking resemblance to one of my favorite NFT projects: QQL by Tyler Hobbs. I don’t know if this is an insult to Tyler or a compliment to the Holiday Inn, but I’m a believer that art comes from unexpected places.

I wrote about QQL shortly after it was released, how much I liked the art and how it represented a new realm of innovation. It has evolved in interesting ways since then and I thought it worth revisiting after a new product launch last week.

Most NFT projects have a “generative” component which means that you don’t know what will come out before it is created. When Bored Apes Yacht Club were designed, Yuga labs established the outlines: here’s the basic ape and then each ape will have seven traits (eyes, hat, background, etc.) and each trait will have a specific style (there are 23 types of eyes: laser eyes, sleepy eyes, sunglasses, etc.) Each has a certain rarity programmed into the generative algorithm and then when the NFT is “minted” (i.e. created), a random seed determines what exact combination of characteristics come out. There is a cap of 10,000 NFTs and once they are all minted, it’s done and you can see the full range of the collection and the actual rarity of each item.

This is how it works for both “fun” NFTs like Bored Apes as well as “art” NFTs like Ringers, Chromie Squiggles or Tyler Hobb’s earlier project Fidenza. But what we discussed last time about QQL was that there was a “choose your own adventure” element to the creation process. When QQL was first sold, users were buying the right to mint a QQL, not a specific QQL generated at that moment. As a mint pass owner, you could then pick attributes of the NFL: the size of the circles, the color pattern, the “turbulence” etc. etc. (you can try the generator here yourself). At the time I thought that was an intriguing, but I guess semi-predictable, innovation. Since then, there have been some follow-on effects from this additional level of abstraction.

First, even though 900 mint passes sold out effectively immediately for around $20K each, only 175 QQLs have been minted so far. In the first month, around 125 were minted, but only 50 have been in the three months since. As a mint pass holder, there are some interesting dynamics. Will my mint pass be more valuable for its option value to create a QQL or as a specific work of art? Will someone discover a new “seed” that will be more interesting or lovely or exciting than what has come along so far? And, pragmatically, if I mint something now, will I eff it up and be pissed at myself for not making something better? Having studied consumer psychology, I think introducing choice into the model is usually more bug than feature, but it adds a layer that further extends the art itself.

Next, on January 27, the QQL team launched a “seed” marketplace. Other artists or amateurs or whoever can work with the QQL algorithm, create a specific output and then store and sell the seed that generated that output. The marketplace has now over 1,200 outputs to browse that are sort of “pre-NFTs.” If you own a mint pass and find one you like, you pay a fee for the seed (perhaps 1 ETH or $1,600) and turn it into an official QQL.

To recap, we’ve got one artist that created the original algorithm and then another artist that created a specific interpretation of that algorithm and then a public that can pick from any of these. I don’t know if all of this is crazy dumb or crazy smart, but as someone who appreciates innovation and experimentation, I’m all in.

◆ Building Blocks

(Big Idea: How Blockchains Work)

OK, now that we have a break from FTX, we can get back to some of the technology behind crypto, specifically, a quirky process called MEV for “Miner Extractable Value” or, more recently, “Maximal Extractable Value.” This is the concept that while putting together a block of transactions, the order in which transactions get executed can be extremely important. In turn, the miner of that block can extract value from that order. We’ll actually come back to that next issue, but for now we’ll start by talking a bit about how blockchains are built.

The way traditional blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum work is that first a transaction gets “signed” by its owner to prove it is real. So long as a user can reach one active node of the network, that node will check the validity of the transaction and then send it on to the rest of the network to get included in an upcoming block. This is called the Mempool and is just a list of all of the valid transactions waiting to get finalized. It’s like when you go to a club and the bouncer checks your ID, but then you have to wait for the guy to take you to your table. Or, like when you go to Palo Alto Medical Foundation and they ask you if your insurance information has changed and you wait to see your doctor yet again. You tell me which example is more relevant to your life.

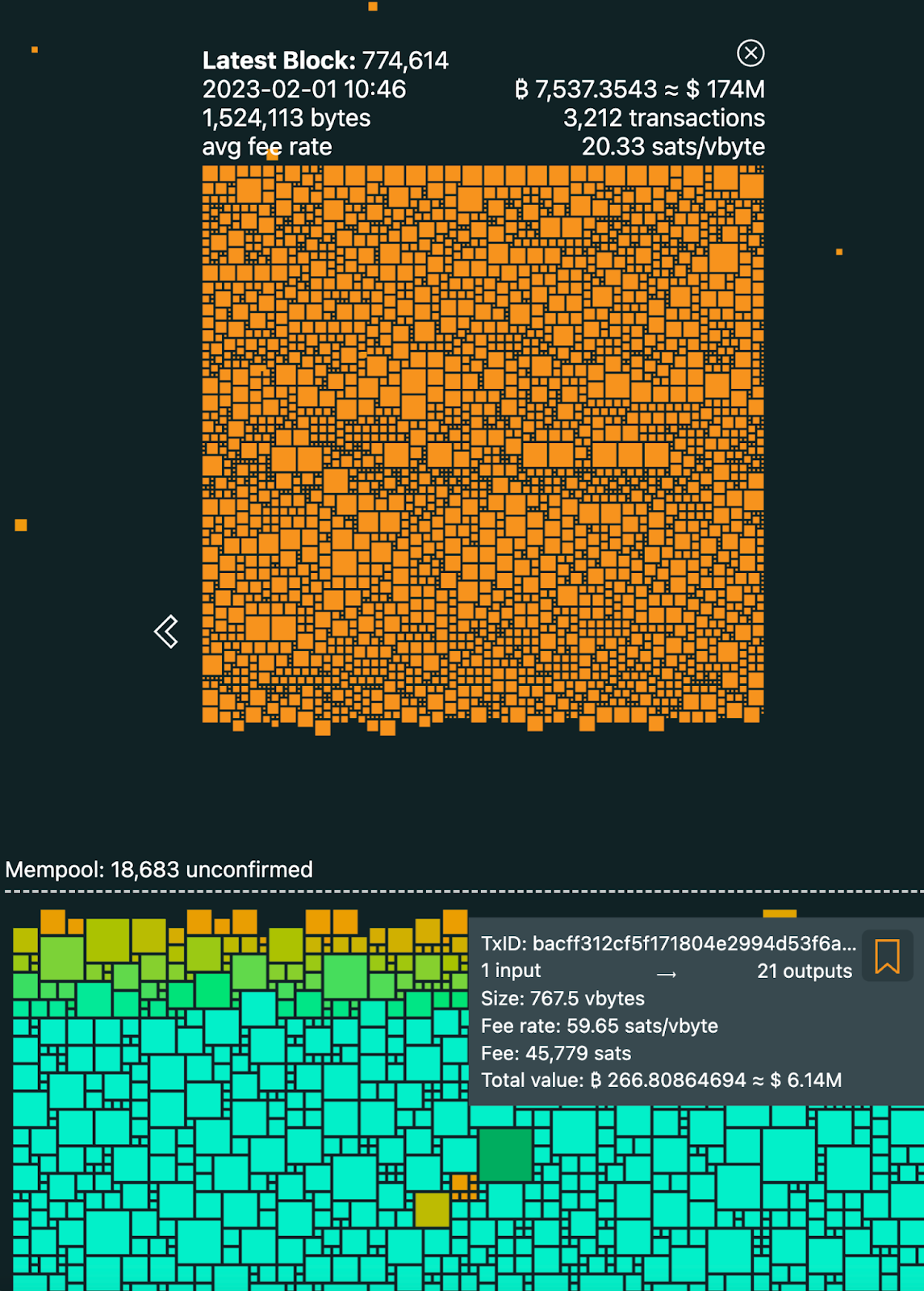

Anyway, this process is easiest to see on Bitcoin since a new block (i.e. an approved and completed set of transactions) comes along approximately ever 10 minutes. This site has a pretty cool visualization of it all:

The top half (in orange) shows a representation of all of the transactions that were in the most recent block. For example, that block included 3,212 different transactions worth a combined $174 million. Below the dotted line is the mempool which at that moment included 18,683 transactions waiting to be finalized. Of them, I highlighted one pending transaction. Transaction bacff312… is attempting to send just over $6 million in Bitcoin from one sending address to 21 different receiving addresses. Included in that transaction was a fee of 45,779 sats that goes to the miner that creates the block. A “sat” is short for “satoshi,” named after Bitcoin’s creator, and is the smallest unit of Bitcoin that can be used: 1/100,000,000 of a Bitcoin. In this case, the fee is around $10. So this user is paying $10 to send $6 million in about 10 minutes, a bit better than a Wells Fargo international wire fee.

While new transactions are flow to the mempool, miners are working furiously to create a new block. At the simplest level, miners look at all of the mempool transactions, sort them by which transactions are offering highest fees and then include as many of those transactions as they can in the next block.

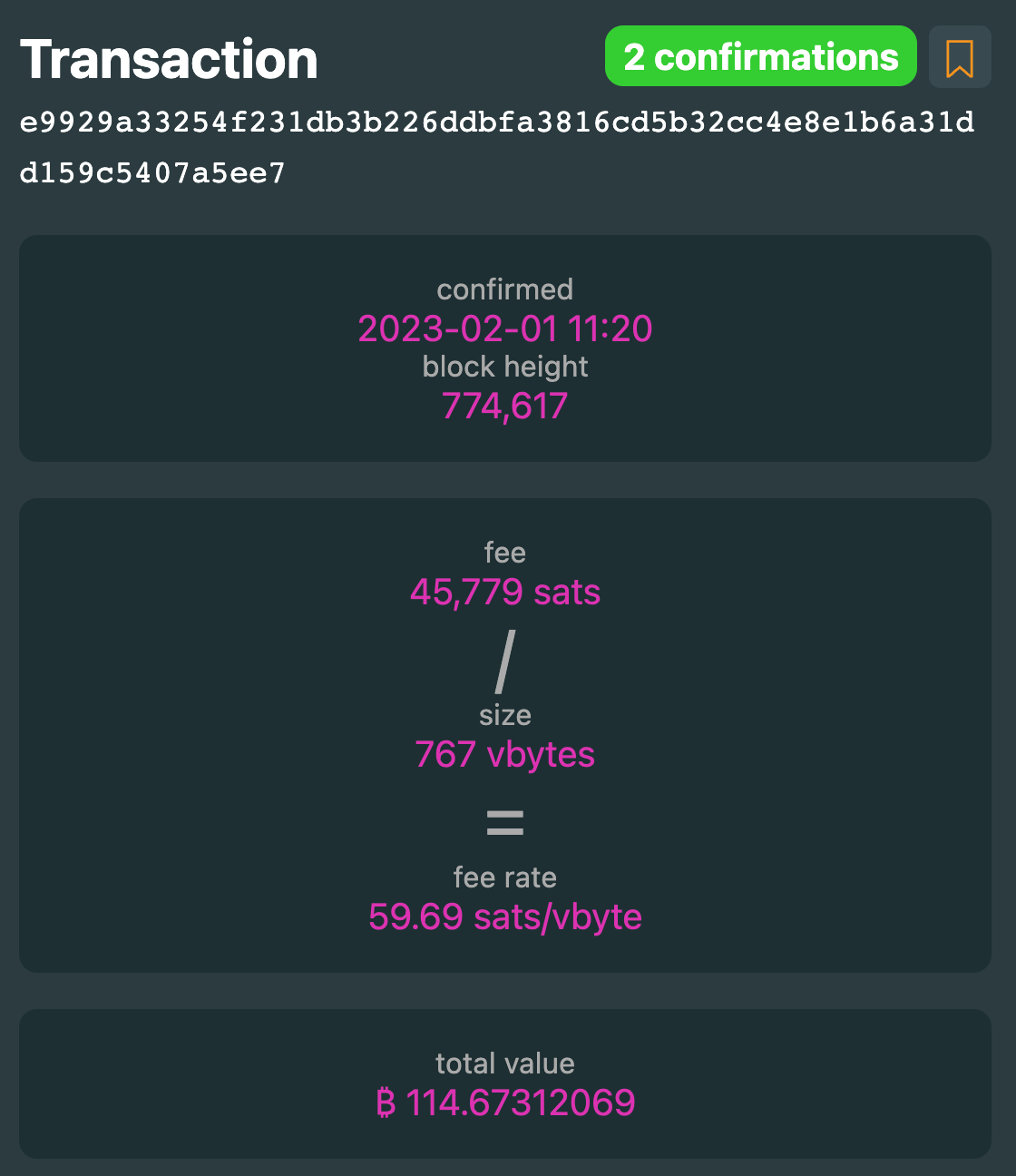

Sure enough, our sample transaction that was waiting before got included in the next block:

Meanwhile, some other transactions will sit there waiting. Right now, I see one transaction that is offering a fee of 124 sats (or roughly $.03) to confirm. That transaction is going to wait at the very bottom of the priority queue and will likely only get included in a block if there are not enough other transactions to fill the block.

The fee mechanism is designed exactly to give users this kind of control. If you have a super high priority transaction that you want to get through quickly, you can pay extra. If you have a low priority housekeeping action, you can put in a very low fee and wait for an empty block. All of this is dynamic based on network traffic. Sometimes, a $10 fee might get you to the very top of the queue (kind of like a Tuesday night at Tao). Other times, a $50 fee might have you waiting a few blocks (more like that famous dermatologist in Midtown).

In Bitcoin, this all works reasonably well and is pretty simple, due largely to the longer block time and limited feature set of Bitcoin. Next time we’ll talk about how this is dramatically different on Ethereum where a single block can contain thousands of complicated transactions and ordering these transactions can have major consequences.

This Week's Freezing Cold Take

The iPhone was announced 15 years ago and Regis, for one, did not like it:

As always, thanks for reading. Send me questions and please share with your crypto curious friends.